Home

Page Back Ground History

Mining Regions

The Postcards

The Tokens

Links

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Site

Forum Cards & Tokens Classified Ads.

Guest Book

Updates & News Contact

The Site

Home

Page Back Ground History

Mining Regions

The Postcards

The Tokens

Links

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Site

Forum Cards & Tokens Classified Ads.

Guest Book

Updates & News Contact

The Site

Home

Page Back Ground History

Mining Regions

The Postcards

The Tokens

Links

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Site

Forum Cards & Tokens Classified Ads.

Guest Book

Updates & News Contact

The Site

Home

Page Back Ground History

Mining Regions

The Postcards

The Tokens

Links

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Site

Forum Cards & Tokens Classified Ads.

Guest Book

Updates & News Contact

The Site

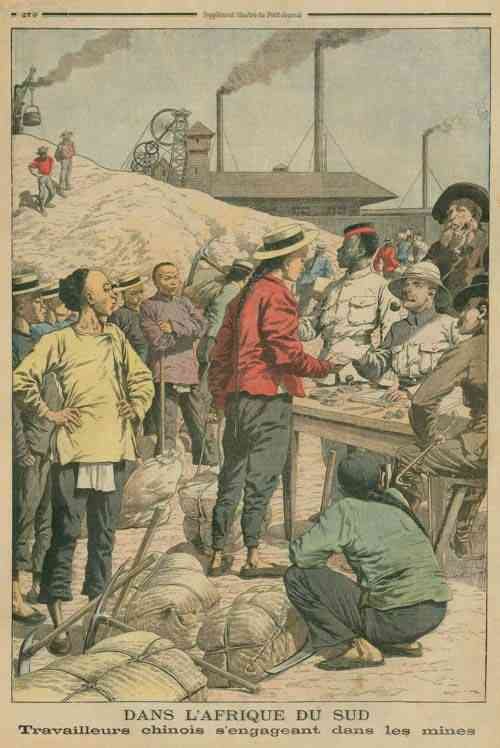

The Chinese On The Rand

Background History:

As the Boer War loomed in 1899, there was a mass exodus of labour from the mines in South Africa, both white and black. As a result all of the mines on the Rand were shut done for the duration of the hostilities. At the end of the war in 1902, both the mine owners and the new British administration in the Transvaal were desperate to get the mines back in production as quickly as possible so as they could re-start producing desperately needed revenues.

Unfortunately with a

general boom in work throughout South Africa after the Boer War there were no incentives

for the African workforce to return to their old jobs on the Rand. Higher paid

work was plentiful in other regions and industrial sectors. The Transvaal

government and the mine owners were forced to take drastic measures to solve the

issue. In so doing they looked to China where there was a large source of

surplus cheap labour in order to recruit a new workforce of indentured

labourers for the mines. In May

1904, the first 10,000 Chinese labourers arrived to work on-the Witwatersrand

gold mines. They continued to come for the next four years and by 1908 their

number totaled nearly 100,000. Most

of the Chinese workers were recruited to serve three to four-year contracts.

They also had to agree to work at special, low rates of pay for at least six

months to pay back the costs of recruiting and their passage from China.

Once

in South Africa the Chinese were treated almost as slaves. Many of them did not

like their new work but were unable to return home. They had no means of getting

out of their contracts, their work was hard, their living conditions basic and

their mine supplied food often sub-standard. Like the African miners, once their

shift was finished their free time was normally restricted to their own specially built

living compounds adjacent to the mines. The compounds were run in a similar way

to those built for the African miners'. Trusted workers were set-up as

"house captains" or compound officials/policemen.

Once

in South Africa the Chinese were treated almost as slaves. Many of them did not

like their new work but were unable to return home. They had no means of getting

out of their contracts, their work was hard, their living conditions basic and

their mine supplied food often sub-standard. Like the African miners, once their

shift was finished their free time was normally restricted to their own specially built

living compounds adjacent to the mines. The compounds were run in a similar way

to those built for the African miners'. Trusted workers were set-up as

"house captains" or compound officials/policemen.

The mine and Transvaal authorities adopted special measures to ensure the Chinese were kept under full control. Despite this they did have limited success on odd occasions in their fight for better pay. One such example was demonstrated in an organised "go slow" in protest of terms and conditions for "hammer men" at the North Randfontein Mine in 1905.

While the Chinese

workers did help in the efforts to get the Rand back into production again after

the Boer War they became a political disaster and

nightmare for the new administration. Many white workers became

concerned about the increasing presence of the Chinese on the Rand. Many were

worried that this new source of low-paid labour would threaten their job

security and wage levels. The Transvaal government helped to ease these fears by

listing 44 jobs, which were reserved for whites only. The Chinese were not

allowed to do any skilled labour, buy land, trade, or pay rent for land. However, an increasing

number of white workers and towns people reacted angrily to the continued presence

of the Chinese. At this time anti-Asian racism and hysteria was at a peak in Anglo-Saxon countries, and the Chinese workers were accused of introducing vices to corrupt the

local population, being disease ridden and rapists etc. The situation was not

helped when growing numbers of Chinese mine workers started to desert from the

mines to live life on the run. Several grouped into outlaw gangs which

threatened the local farming communities. This spread yet more alarm and threat

to the Transvaal communities and government.

In Britain the question of the Chinese workers in South Africa became a major political issue. Trade unionists and

many Labour Party politicians supported the white miners and condemned the use of Chinese labourers. In fact, the issue was exploited very broadly by both the Labour and Liberal Parties and it added to the growing unpopularity of the Conservative-Unionist government.

Eventually, the various campaigns in both South Africa and Britain which were

apposed to the use of Chinese labour on the mines were so successful that the

Transvaal Administration was ordered to stop all further

contracts. All the Chinese workers in South Africa were to complete their

contracts and were then to be repatriated to China. The last batch of Chinese

workers left South Africa in 1910.

The Postcards

Although the Chinese spent only a comparatively short period on the Rand their stay represented an important period in the Goldfield's history. This is reflected in the number of postcard issues that relate to them. These cards cover all aspects of the life of the Chinese from their arrival on the Rand; their working lives; living conditions and recreation time through to their departure from South Africa. Like the native African miners, the Chinese workers were forced to live segregated lives while on the Rand. Their lives outside of work were restricted to closed living compounds. Each mine having separate compounds, one for its African the other for its Chinese workers. Many of the postcards from this series represent the different aspects of life in these Compounds.

Notes:

1) For further information and enlarged views of each postcard click on any one of the above images.